| Memoir of the Year |

Theatre Writer Book |

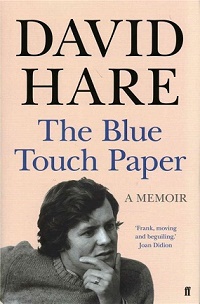

| David Hare “The Blue Touch Paper” , Faber & Faber , December 8, 2015 |

David Hare and I go back a long way. Or rather there were two of them, two Davids. . When I was readying for adult life, in my own way, the two Davids were there. Edgar and Hare seemed to speak of the world as it seemed to me. In particular, the television film “Licking Hitler” was broadcast in a winter when my own life was dull. Its message, the heinousness of public school men, felt right. My own experience had been that public school men were a lordly caste, seeped in self-entitlement. Nuance and a greater tolerance were to come later.

David Hare and I go back a long way. Or rather there were two of them, two Davids. . When I was readying for adult life, in my own way, the two Davids were there. Edgar and Hare seemed to speak of the world as it seemed to me. In particular, the television film “Licking Hitler” was broadcast in a winter when my own life was dull. Its message, the heinousness of public school men, felt right. My own experience had been that public school men were a lordly caste, seeped in self-entitlement. Nuance and a greater tolerance were to come later. Hare from the public biography was one of them, a Lancing man gone surely, in the eyes of his class, to the other side. The first surprise, and one that persists throughout “the Blue Touch Paper”, is how wrong was that judgement. Hare was just the local Sussex boy who scraped in and liked it little. The food comprised “a great many curried eggs, slimy fish roes, soggy toast with margarine, cold sardines and twisted slabs of rank haddock. Everything came with a crust, a skin.” W H Auden said that he understood the totalitarian states of the 1930s- public school had been his tutor. At Hare's Lancing “fags were known as underschools and lavatories were groves. Everything was in code, and the code had to be learnt. Some of the rules seemed to defy explanation. Maybe that was the point.” The apposition of the bright boy within the classroom and the socially lost one without left its mark for life. Graham Greene, he says, made his unpleasant characters Lancing alumni. It stood for “a particular sort of aspiring public school that produced a young man full of facile sociability and doubtful morals.” Those doubtful morals fuelled the drama for a half-century to come. Hare was precociously successful in theatre. Becoming the Royal Court's literary manager at the age of twenty-one did not seem in any way remarkable or precocious. “No-one else wanted the job.” The three-day a week job paid £7.50. He met collaborators early. Snoo Wilson: “an eccentric and highly charged student...Snoo had a shock of unruly brown hair as if someone had just given him fifty volts”. In the era that Portable Theatre was formed it was one of “more than seven hundred theatre companies formed all over the UK- as if small-scale plays- confrontational, angry, direct- might somehow reach a gap in an audience's concerns that nothing else was filling.” It is a truism of Hare that the state has been of kindness to the author who stridently dislikes it so much. The Arts Council of England, under master-fixer Lord Goodman, was generous towards Joint Stock. Simon Callow wrote of “Fanshen” that the production “had changed everybody's lives in almost every way.” In Hare's account, absorbing as it is, “Fanshen” lacks the close-up conclusion of Simon Callow. Beneath the ferment, the discussion, the participation, what the company did was what the directors wanted to do. Memoir merges inner and outer world. A play of Snoo Wilson's required a goat. It lived in the Hare garden and each night for six weeks it was pushed into the back of a Citreon 2CV to go the theatre. The Theatre Upstairs at then Royal Court was up a flight of seventy stairs. Hare's politics were set for life by 3rd May 1979. On a single day an entire population passed from solidarity and collectivism to its venal opposite. The book reveals that Hare had not been in Britain in the time before. He had been in New York City. He had been back just four weeks so the Conservative victory “made no sense to us.” It never has. Into the 1980s' Hare surveys the hedonism of the time before AIDS. Of New York's most notorious location for orgies he writes “the likely drawback was that the first person you would meet would be a British theatre director.” The book does end in somewhat of a rush. The Adelaide Festival in 1982 was responsible for “A Map of the World”. At the time it felt thrilling to see, more so than the cartoonish “Pravda.” The critical high-points, the Eyre trilogy of the 90's and “Skylight” get hardly a mention. Right to the end the pain of the father absent to the child is constant. The last line reads “Almost a hundred years ago my father stole walnuts under the spreading tree in Chigwell. Today I walk the hills and dream new ideas.” The most striking revelation about the inner life is the vulnerability. On page 2 he writes that “the very over-sensitivity that equips you to be a writer also makes being a writer agony.” Like Callow's memorable description in his memoir of self-finding in acting Hare writes memorably on writing. “Only when I became a creative writer could I rid myself of self-consciousness, and of worldly ambition.” The paradox of creativity is once again reprised, that fulfillment of self entails an unselfing. “The page fills or it doesn't. You're powerless.” Hare describes a literary equivalent to what is known in theology as kenosis. “You can't force it. If you did try to force it, if you wrote words which did not convince you, a strange feeling, rather like an elephant sitting on your chest, would begin to oppress you. Far from frightening me, this revelation of powerlessness set me free. Because I was no longer in command, I was able to stop worrying about the effect of what I was doing.” The cost that writing demands passes into illness. The physical toll on the young man is revelatory. Hypertension stalks. Once during technical rehearsals an actor says “oh, if it's seven o'clock, you'll usually find David being sick in the Gents”. He reports a terrible pain while walking up Sixth Avenue. The prevailing over-sensitivity of the writer is contrasted by a conversation with Lord Goodman (1913- 1995). “Let's get this clear from the start” he informs the artist “I'm not worried about anything. If I worried, I wouldn't sleep at night.” |

Reviewed by: Adam Somerset |

This review has been read 228 times There are 35 other reviews of productions with this title in our database:

|