What's My Motivation?- Michael Simkins |

The year of clearing out the critical cupboard cannot pass by “What's My Motivation?” If this is the last review of a book by an actor, so it is also one that matters. It was first published in 2003 and republished regularly. Many actors have read Simon Callow, below July 2014. “Being an Actor” has a durability to it, but Michael Simkins' book is the one to cherish.

The year of clearing out the critical cupboard cannot pass by “What's My Motivation?” If this is the last review of a book by an actor, so it is also one that matters. It was first published in 2003 and republished regularly. Many actors have read Simon Callow, below July 2014. “Being an Actor” has a durability to it, but Michael Simkins' book is the one to cherish. At the top of the Amazon feedback an actor is there to testify: “I am in that business that we call show and absolutely love this book. I found his account of 'living the dream' gorgeously nostalgic and wonderfully warm, honest and witty. I think that it would be very insightful for a layman to read as well as those of us who are already hardened and softened by the realities of being an actor.” The narrative arc of “What's My Motivation?” follows thirty years of autobiography, told sharply and colloquially but shot through with a tone of self-deprecation. It is far remote from any roll-call of triumphs and celebrity encounters. Simkins pinpoints the lures of infidelity while on tour. In his time, to get car insurance for an actor was an appalling hurdle. That may have altered but much else is unchanged. Pantomime is crucial for paying a large slug of venues' fixed costs. Actors are ripe for pummelling by managements. The hazards of the acting life are as numerous as they are varied. Simkins must be the last word on the terrible fate of the poor players who encounter the Director with the Concept. And all the time, for the reader, it is squirmingly comic. As a tale it ends well, on a high, acting alongside Malkovich in “Burn This”. If Simkins is finally there for a sell-out at the Hampstead Theatre, the route has been via Hornchurch, Harrogate, Billingham-on-Tees, Poole. He describes a journey from Potters Bar to Middlesbrough. A fellow cast member owns a VW Beetle to share the cost. But its floor has a hole in it and the mats rise on an inch of water. In a life of uncertainty the pursuit of love too is uncertain. But the Simkins romantic life also ends happily. “What's My Motivation?” does not flinch at the reality of the profession of actor. “The same 10% of actors”, says Simkins, “tend to work all the time, the rest spending their entire lives working in bookshops, driving delivery vans or waiting tables.” But he also makes the clear observation. “Talent has nothing to do with it- apparently strategy and luck are what you need.” In the pub Simkins sees “middle aged blokes in balding corduroys and Dr Who scarves, who daren't risk having to buy a round of drinks, and talking about the big break that is just around the corner.” It would be a spoiler to reveal too much of what unfurls in the chapter called “Bear”. Simkins starts with: “there are two types of director. Blockers an w***ers”. They are not in the habit of winking. The actor has a nice job, a Shakespeare tour, and meets his director. “Simon is an unusual hybrid in that he's both a blocker and a w***er. That takes some doing. He's spent two weeks sitting round a table pontificating on the various allegorical allusions and classical references, and then has lost his nerve in the final few days pushing us around the stage hysterically.” Not in the pub Simkins meets Rob. Rob “earns between eighty and a hundred grand a year, a house in Leeds, a flat in Crouch End, a Spanish timeshare, a vintage sports car and a Harley Davidson.” And with no mortgage he is set to retire at age 30. The sources have included Campbell's Soup, Domestos, the RAC, Carling Black Label, a clinic specialising in the treatment of leg ulcers. “Rob”, says Simkins, “finds my interest in theatre rather quaint.” The book is a universe away from the world of scholars and critics. When the actor gets Tony Wendice in “Dial M for Murder” for a long run it is great. There are lots of lines, high exposure, and it's a good plot. It is the strangest of life-choices. To head for work, if it is there, when most of us are piling out of our own work-places makes for separation. Towards the end, with a settled domestic life, a social event is recounted. Neighbours come in, a young couple from Camden social services. They speak with passion about their own jobs. But the host, an actor, has old editions of “Spotlight” on her shelves. The actors pile in to see their images of old. As for the non-actors “we'd forgotten them in all our excitement. They were looking forlornly across from the opposite settee.” The public-minded spirits who flock to Boards and Councils may regard actors as a sub-strand augmenting other areas of public activity. Wrong. They are not there as part of the education, health or social services. They have chosen their lives to give us delight and to give us meaning. This is triumphantly their book. Acting ISBN: Eburypublished:

|

Looking for theatre books? Try the Internet Theatre Bookshop first                                  |

The Cambridge Introduction to Theatre Studies- Christopher B Balme |

“Theatre, no longer needing to be a mirror to society...”

“Theatre, no longer needing to be a mirror to society...”An observer of performance of Wales cannot leave the critical stage with Theatre Studies left unmentioned. They have been of influence here, to small advantage, in a way that Scotland and England have been, to a greater extent, immune. To the history: if I lean leftward from my place of writing a mini-roundabout comes into view. Remarkably for a county with only a 72,000 population, the road west leads 14 miles to a university, and the road north 16 miles to another university. At the turn of the century the first had a Professor of Theology and the second a Professor of Drama. I was friendly enough to exchange words with both when our paths crossed. Both these professional titles have now gone, their successors holding Chairs in Religious Studies and Theatre Studies. Their concerns are different, the objects of their scholarship pivoted elsewhere. Theology and drama were for long historically much the same thing. Their interests are not so far apart, grace, destiny, teleology, conscience among other things. The divine was a powerful presence in the foundational dramas, there still in three of the national company's inaugural Year of 13. These are domains where Theatre Studies do not like to travel. In fact its consideration of theatre, which is an aesthetic phenomenon, is skewedly non-aesthetic. Page 12 Professor Balme, himself of Munich University, refers to Richard Schechner. (This is not intended in denigration of a scholar who is of the highest standing.) “Schechner demonstrated in numerous publications the interdisciplinary potential of such a concept, and emphasised its status as a social science rather than as a branch of the humanities. The definition of performance within the broader parameters of the social sciences implied a departure from aesthetic and historical paradigms.” Performance criticism becomes then a rational-evaluative activity. But it cannot sit comfortably with the social sciences. They are, as the title says, sciences. Their method is based on rigour, experimental design and practice on a foundation of statistical discipline. These methods are not applicable to criticism because performance remains an aesthetic phenomenon. The second point of rebuttal is derived from neuroaesthetics. Attendance at performance is a sensorial and not just an upper cortical activity. It really is the almond and the seahorse. An evaluative approach that avoids this is lacking in fullness. Theatre Studies, nobly ambitious in its origin, has diverged into various currents. One contains an inherent loftiness, and daftness. Thus a Theatre Studies lecturer can declare “A piece of performance art and cultural nourishment can not be satisfactorily explained in common words.” This is false. It is description, evocation and evaluation. “It's impossible to accurately convey the texture, aroma and inspiration behind each piece of reflective work. Such crude and simplistic descriptions are better suited to the right wing populist drivel beloved by the masses.” I care little for this tone and even less its extension: “Theatre, no longer needing to be a mirror to society and realistic, a job better done on a global scale by television, has now developed into an art form in which the theatre space becomes the exhibiting gallery, its audiences an informed few.” Whether this is a widely held view among the scholars of theatre is known only to themselves. By way of a seasonal item: Question: How many Theatre Studies lecturers does it take to change a light bulb? Answer: Interrogation into those elements of the illuminatory act, that are qualitatively dimensional- necessarily to be understood as always provisional, temporal, capable of reverse- by definition refers to relation, the act itself being refutation of any Kantian an sich selbst restriction, given that the act is dependent on the co-presence of a space that necessitates illumination. The very necessity of that three way contextualised interdependence- the space that in its preliminary condition requires illumination, the source of illumination itself, and the intermediating action, itself expression of human agency- engenders consideration of possibilities that this is less an issue of “switch the blooming light on, will ya?” than a tentative adumbration, calibration, encirculation of the considered potentialities that the act may entail elements with potent overtones of performative complexity. An opening enquiry must look to these situational hermeneutics, not least to issues of identity- who is the human actor seeking the benefits of illumination, and is that beneficiary to be automatically understood as consistent, or variant, from the human identity that is intended to execute the performative illuminative act? Walter Benjamin- and it is significant that his editors entitled his essays “Illuminations”- offers insight to these inherent tensions between actor and potential acted-upon. If this is to privilege the actor, the agent acting upon the “switch”, an understanding from a Debordian perspective is corrective. But these considerations are in themselves subordinate to a cultural overview, that the presupposing requirement for illumination is itself dependent on a culturally determined defining that one condition be initially categorised as “dark”, with the second condition, resonant of a Lacanian “mirror”, that a declared “light” be pre-understood as remedial, reparative, ameliorative. Thus, from a Bourdiau-ian perspective, the very act of request that the light be changed becomes itself indicator of a hegemonic privileging, even prior to the questioning of the process of tacitly constructed metaphorisation whereby a product of mass manufacture becomes acquiror of characteristics from the natural world, endowed by the signifier “bulb.” This in turn raises deeper questions, addressed by Baudrillard, although first Saussure’s crucial distinction of signification asserts itself… (Now we’re all in the dark.) critical comment ISBN: Cambridge University Presspublished:

|

Looking for theatre books? Try the Internet Theatre Bookshop first                                  |

Better Living Through Criticism- A O Scott |

From the USA: “The administration has systematically destroyed our confidence in its credibility and good intentions, perhaps in the democratic process itself.” It is a common voice of despair which might have been written anytime in the last two years. In fact not so; the author was the theatre critic Robert Brustein in an essay “the Unseriousness of Arthur Miller.” He was writing in 1967 and his article is one of 39 collected in “the Third Theatre” published in 1970.

From the USA: “The administration has systematically destroyed our confidence in its credibility and good intentions, perhaps in the democratic process itself.” It is a common voice of despair which might have been written anytime in the last two years. In fact not so; the author was the theatre critic Robert Brustein in an essay “the Unseriousness of Arthur Miller.” He was writing in 1967 and his article is one of 39 collected in “the Third Theatre” published in 1970.It came to mind when reading another article, this time published by Exeunt magazine on 22nd October of this year. Its topic was quality in theatre and who are its adjudicators. It picked a gender fight on newspaper critics for being all the same. As an argument it looked threadbare, since the best of theatre writers- McMillan, Marlowe, Brennan, Clapp- are women. But it called for new modes of response without specifying what they might be. But in particular the word “old” was used as disparagement. Well, Robert Brustein is old, born in 1927, and so is James Roose-Evans, also born in 1927. To read Brustein at the Open Space and the Living Theatre and to read Roose-Evans on Bread and Puppet Theatre is to have events and experiences evoked that thrill across the decades. The adrenalin of the productions makes today's concerns seem anaemic. To disparage the old is to give to the present a superiority that is invalid. The tyranny of the present is a burden better shaken off. A O Scott, long-standing film critic for The New York Times, certainly is unchained by the present. His six chapters- interrupted by three Socratean dialogues- have titles such as “The Critic as Artist and Vice Versa,” “the Eye of the Beholder” and “How to Be Wrong”. His vaults across time go to Hesiod, Plato and Aristotle, Horace and his “Ars Poetica,” Kant is invoked: “The judgement of taste is not an intellectual judgement and so not logical, but is aesthetic- which means that it is one whose determining ground cannot be other than subjective.” Kant's three-part philosophical hierarchy, the ascent from sensation to reason, begins with “the agreeable.” If subjectivity is the ground then the consequence is inevitable. So, as Scott puts it, “the history of criticism is, in large measure, a history of struggle among various factions, positions, and personalities, of schisms arising from differences of taste, temperament and ideology.” Their reception straddles the respectful to the scornful. In 1921 T S Eliot, a powerful critic himself, is referring to the others as “no better than a Sunday park of contending and contentious orators, who have not even arrived at the articulation of their differences.” Art, a dialogue across time, binds the centuries. Scott looks at Manet “conducting a passionate argument with Titian and Velázquez,” “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” is an engagement with the masks and statuary of another continent. He is sharp on Marina Abramovic and her “The Artist Is Present”. Some who were in New York's Museum of Modern Art were prompted to remove all their clothes. Scott is moved to link the performance art-piece to Rilke's poem “Archaic Torso of Apollo.” “Better Living Through Criticism” recalls the critics who have nourished the author himself. “I read Stanley Crouch on jazz, Robert Christgau and Ellen Willis on rock, J Hoberman and Andrew Sarris on film, Peter Schjeldahl on art. Also C Carr on underground, avant-garde theatre and performance art. I didn't know that the C stood for Cynthia.” He confesses that he never worked up the nerve or saved the money to get to the city to see Ontological-Hysteric Theater or Laurie Anderson or David Wojnarowicz or Alphabet City. In reading Carr “what won me over was not the force of her ideas but the charisma of her voice.” Scott cites the caustic metaphor of fiction's greatest theatre critic, Addison de Witt. In 1938 he finds a great poetry critic, R P Blackmur, saying “criticism, I take it, is the formal discourse of an amateur.” But then amateur has two meanings. Scott adds his own lines that might have sprung from de Witt: “the critic is therefore a creature of paradox, at once superfluous and ubiquitous, indispensable and useless, to be trusted and reviled.” “Better Living through Criticism” is discursive, precious on occasion, but diamond-hard at its centre. In dialogue the author answers his own question to the effect that “criticism was perfectly satisfying in its own right- complete and fulfilling enough to make anything more seem superfluous.” The book's central platform elevates the writing to a status of equality to that which is its subject. “Criticism is art's late-born twin. They draw strength and identity from a single source, even if, like most siblings, their mutual dependency is frequently cloaked in rivalry and suspicion.” This equality has another dimension, that of codependency and symbiosis. One activity receives its full consummation by way of the other. “Criticism”, at least in the view of Scott, “far from sapping the vitality of art, is instead what supplies its lifeblood.” It is “not an enemy from which art must be defended, but rather another name-the proper name- for the defence of art itself.” We are a long way from the notion of a review. Scott sees a commonality in motive. Both art and criticism originate in “the urge to master and add something to reality”, their wellspring the “transformation of awe into understanding.” critical comment ISBN: Penguinpublished:

|

Looking for theatre books? Try the Internet Theatre Bookshop first                                  |

The Arts Dividend : Why Investment in Culture Pays- Darren Henley |

Arts Councils produce their documents but the opportunity to look behind the curtain is unusual. Darren Henley of the Arts Council of England in 2016 offered a crisp description, from a personal rather than an official perspective, of the place of the arts within the public domain.

Arts Councils produce their documents but the opportunity to look behind the curtain is unusual. Darren Henley of the Arts Council of England in 2016 offered a crisp description, from a personal rather than an official perspective, of the place of the arts within the public domain. It is a truism to say that the arts are various, in mode and form, scale and aspiration. Henley tackles a generally held dichotomy early on. “I don't understand the distinction some make between “great” and “popular” he writes. ”There are works of art that are ahead of their time, but few artists have striven not to be read, or to have their work leave people untouched. The greatest art is the most human. Given time, it will always reach its audience.” That is a bold statement. The theory is nice although there is no guide to arts managers over selection. To fund or not to fund is still the question. Common words assume lethal meaning in discussion in the subsidised sector. “Accessible” has a pally ring to it. Lee Hall has written plays that have been seen by a lot of people. “Accessible”, says Hall, “is a lie perpetrated by those who want to sell us shit. Culture is something we share and we are all the poorer for anyone excluded from it.” Henley even kicks the word “subsidy” itself into the long grass. “But there's no subsidy. Personally, I cannot abide the term”, he says, “The Arts Council doesn't use public money to subsidise art and culture- it invests money for the benefit of all the public.” But each work attracts its selective public. The important thing is that there be a rich ecology, more easily achieved in a large jurisdiction like England than the vastly smaller ones of Scotland or Wales. Quality surely ought to be a yardstick. But aesthetic judgement over contemporary arts is a semantic and conceptual quicksand in a territory where authority is uncertain. Commercial interests loom. A strand in higher education pitches in, high in reference and vocabulary beyond the layman. Haptic, anyone? Yet at times the smell of lobbying pervades. Critics divide. Sometimes they indulge in a bout of collective breast-beating. The long-term valuation of “the Homecoming” was not that of the reaction at the time when it played Cardiff’s New Theatre. “We were all wrong” writes Michael Billington on page 355 of his authoritative book “State of the Nation.” Artists ought to be predictable and they are not. In 2018 Martin McDonough is at the top of his game in film. His return to the stage, at the Bridge, has been met with critical loathing. In his book Henley visits the fifth Manchester International Festival. The credits for “wonder.land” are formidable: Damon Albarn, Moira Buffini, Rufus Norris. When it arrives six months later at the South Bank it gets a one-star critical pounding. Henley cites Peter Bazalgette’s first speech as Arts Council Chair. “The arts create shared experiences that move us to laughter or to tears.” But sharing is a concept where the numbers are shrinking. Fin Kennedy has been charting the inexorable shift in England’s spending year on year away from theatre located in auditoria. The reasons are several, aesthetic fashion among them. Innovative form in one viewer’s eye is gimmickry in another. But formal novelty has a trend to drive down spectator numbers. The audience size which now gets to see Punchdrunk has fallen, the prices have soared while the critical enthusiasm has sagged. Henley in his book travels widely both geographically and historically. He is enthusiastic about Manchester. The city under the regime of Leese and Bernstein has a sterling reputation for its quality of governance. He does not visit the West Midlands where the same does not apply. Birmingham Repertory Theatre has the greatest historical stamp of any theatre outside London. The city no longer provides the level of funding to cover the maintenance on the building that it owns. In the north-east he visits the Woodhorn Museum where the paintings of the Ashington Group are displayed. He is there because “the Pitmen Painters” toured the UK and did Broadway. But the group were amateurs and the paintings are those of amateurs. The one exception is Oliver Kilbourn who stands far above his friends. The historic interest of the Group is considerable but the artistic achievement overall is not. Henley draws from the work done by his council. In the chapter “the Learning Dividend” he cites an ACE report from 2014 that taking part in drama and library activities improves attainment in literacy. Taking part in structured music activities improves attainment in maths, early language acquisition and early literacy. From the Cultural Education Challenge he repeats its conclusion: “every child should be able to create, to compose and to perform in their own musical or artistic work.” In the United Kingdom the schools in the Fro are alone in this. The book holds up well although the chapter “the Innovation Dividend” will not be read in the same light. Back in 2016 it was an easier and a more innocent time for the globe-spanning tech platforms. Streaming of arts events has been good for the rich. The prestige companies in opera and theatre have found themselves new audiences in cinemas around the world. The phenomenon is led by stars. Small organisations are crowded out. The Hampstead Theatre claimed remarkable numbers for a Stella Feehily play. But dipping in on a small screen does not mean lasting the full two and a half hours. “The Arts Dividend : Why Investment in Culture Pays” says a lot, as much as any insider could put in as a statement of belief. But at the same time as it says everything it says nothing. In a culture of profusion the demand for funding, whether it be called subsidy or investment, outstrips supply. Arts Councils are allocation bodies. And to be in the public realm adds another dimension of complexity. To the outsider with no knowledge it is likely that decisions are reached in a way similar to other organisations. Habit, past practice, new ventures, compromise, balance, prior reputation, variation, social amelioration, bias, lobbying and politicking are all in the mix. D W Winnicott, the great child psychologist who became a surprise best seller, popularised the notion of “the good enough mother.” By analogy let the funder-rationer-allocators aspire to be the “good enough arts council.” That is good enough. historical surveys ISBN: Elliott and Thompsonpublished:

|

Looking for theatre books? Try the Internet Theatre Bookshop first                                  |

Now You're Talking- Edited Hazel Walford Davies |

"Now You're Talking” (2005) is the last book to be published in Wales on its contemporary theatre. The excellent “the Actors' Crucible”, reviewed November 2015, is principally a retrospective. “Now You're Talking”, inevitably for Wales, had its source in public sector action. In 1993 the members of the Drama Panel of the then Welsh Arts Council were concerned that theatre practitioners in Wales lacked a forum for debate.

"Now You're Talking” (2005) is the last book to be published in Wales on its contemporary theatre. The excellent “the Actors' Crucible”, reviewed November 2015, is principally a retrospective. “Now You're Talking”, inevitably for Wales, had its source in public sector action. In 1993 the members of the Drama Panel of the then Welsh Arts Council were concerned that theatre practitioners in Wales lacked a forum for debate. New Welsh Review was provided with resources to produce a Theatre Supplement. They may be read on this site, the link being fifth from last to the left on the navigation column. Over the course of this period Hazel Walford Davies interviewed the dramatists of Wales. 15 feature in “Now You're Talking.” The speaking voices are all distinctive and enlivened, cumulatively coming to form a vivid picture of an earlier time in Welsh theatre. The tonal range is considerable, irritation and vexation at one end to accomplishment and pride. Dic Edwards recalls that the BBC once wanted to enliven drama. His choice of subject, narcotics in the Valleys was not wanted. Frank Vickery puts in a reminder that he was translated into Welsh, Gaelic, Spanish, Frisian. An earlier cohort of dramatists went out into the world. Mark Jenkins was performed in the Sidney Opera House. Unexpected elements of biography appear. Greg Cullen spent a year and a half in Angola in the employ of a company that flew Hercules transport planes. Gary Owen spent a period in Jutland. Chapel is supposed to be a source for culture, in music at least. For Sion Eirian religion is the opposite of morality. “What I found in that upbringing as the son of a minister...was that it stultified anything creative...the writing was more to with what I escaped from.” There are comments on the craft. Sion Eirian: “philosophy especially helps one to train and structure ideas and in the dialectic that always exists within dialogue itself, let alone within the general shape of a play.” Charles Way says rightly that theatre goes into an emotional place that is beyond words. Greg Cullen: playwriting requires “a cool head and a passionate heart.” This was the period when discussion of a national theatre was a constant. The people of Wales, says Charles Way, are dispersed. Theatre needs to “go to them and be part of their lives.” Lewis Davies looks forward to a national theatre doing revivals of Alan Osborne- “that kind of production would certainly draw audiences.” “Those who plead for a National Theatre and do nothing to feed the roots are self-serving individuals” speaks another voice. Dic Edwards: “I think that a Welsh National Theatre would be a disaster.” The critics of the time get their drubbing: “To engage in reading criticism is often to wade through an awful load of rubbish and I have to say that people who review for newspapers in Wales are generally not very good. “Billington and a few other reviewers in England really care about theatre. That isn't the case in Wales. In fact, if you're a dramatist here and have any sense you probably won't read the reviews in “the Western Mail.” You can get wound up by the stupid things that are there. It's best to make a decision to ignore reviews and put your energy into your work. Writers need to have respect for professional reviewers who can give them informed and objective feedback. But that respect needs to be earned. It's certainly not earned at the moment.” Some things endure. The media in England mainly dance to the PR piper. Ed Thomas: “the reality is that when it comes to our profile in the UK no-one cares whether we exist or not.” historical surveys ISBN: Parthian Bookspublished:

|

Looking for theatre books? Try the Internet Theatre Bookshop first                                  |

The 101 Greatest Plays- Michael Billington |

“The 101 Greatest Plays” was published in 2015, the weightiest book of its year. It went unreviewed here at the time but appears now as part of the process of wrapping-up. Any book that comprises a list provokes a first reaction: to go in punching. There will always be objections to choices for inclusion and equally exclusions that are blatantly absurd. The very act of selection provokes.

“The 101 Greatest Plays” was published in 2015, the weightiest book of its year. It went unreviewed here at the time but appears now as part of the process of wrapping-up. Any book that comprises a list provokes a first reaction: to go in punching. There will always be objections to choices for inclusion and equally exclusions that are blatantly absurd. The very act of selection provokes.Joyce Macmillan wrote a reliably punchy review for the “Scotsman.” She ends with “Billington’s enthusiasm remains undimmed; as does the elegance and vigour of his writing, which – backed by his unparalleled banks of theatrical knowledge and wisdom – makes these essays a joy to read, even while we rage and quibble over Billington’s choices, and set about compiling lists of our own.” She has it perfectly. Before that conclusion Macmillan picks out the factors that underlie. “It is therefore essential”, she writes, “to point out that Billington’s choice has an unsurprising bias towards the English stage, and is almost exclusively focused on the theatre of the western hemisphere. There’s no attempt to include any classic work from the repertoire of Noh theatre or any other eastern tradition; and even within the western canon, it’s clear that a similar list produced by a French or American critic would look very different.” In fact there is a generosity to Germany with Lessing getting in. Schiller and Kleist both contribute a couple each to the best 101. Macmillan, a fiery reporter from her own patch, observes: “as for Scotland, it barely features at all; indeed of all the plays created and produced in Scotland since mediaeval times, only Ena Lamont Stewart’s great 1947 drama “Men Should Weep” makes the final list. Nor does the list feature many other women playwrights, although Billington seems to strive.” Her strongest objection is reserved for “it’s astonishing, given his generally left-leaning sympathies, to see nothing here of either John McGrath or Joan Littlewood, the two great pioneers of radical British theatre in the 20th century.” Surprisingly, the theatre of Wales appears not just on the first page but as the first line. The reason is the year of Aeschylus' birth and thus the opening of the book. “We gathered in the Brecon Beacons on a sunny August evening in 2010 to see the oldest surviving play in Western drama. No-one who was there will ever forget Mike Pearson's production.” The essay that follows is a model for the 100 that follow, a wide-ranging view across four translations and three productions. The scale of the learning is formidable, the range of experience unique. He has simply been there for a length of time without equal. He was there to review two radio plays from a new name. The titles were “If You're glad, I'll be Frank” and “the Education of Dissolution of Dominic Boot.” The year was 1966. So the book is to be read for what it is, ever elegant and eloquent, with an underlying aesthetic, and moral, bedrock to it. The approach is clear from the introduction. Billington is no "interrogator" of “text.” “The book is not a study of plays on their own. Their experience is not inseparable from their enactment. The experience is their enactment.” So,the aesthetic point revealed on Mynydd Epynt is: “what we discovered- or at least I did- was that Aeschylus from the start had unearthed a fundamental principle of drama: that it should contain moral and political ambivalence and that its meaning should vary according to circumstance.” The same point is repeated 343 pages on in the first line on “the Crucible”. “Great plays change their meaning depending on time and circumstance.” These aesthetics are elaborated in discussing Frank Wedekind. “I hope I've made clear my admiration for naturalism, a movement that turned drama and fiction away from the purple excesses of romanticism and allied them to a Darwinian spirit of scientific enquiry.” Page 335: “by now the basic qualities that I look for in a great play should be fairly clear. I seek the smell of reality, a clearly defined social context, vivacity of phrase, moral ambivalence, a fluctuating tragi-comic mood.” In a stimulating demonstration of contradiction he goes on to select Ionescu who embodies none of these qualities. The book never lets us forget that theatre is an event with the critic a live presence. “It was one of those nights no one who was there will ever forget: 4th July 1997.” Read the book to know the what- as a pointer Ian Rickson was directing. In ranging far and wide across “the Cherry Orchard” he remembers a director who has a branch fall climactically through a window next to the abandoned Firs. That was Peter Stein for the Berliner Schaubuehne in 1989. Solipsism in online writing on theatre is a default, the intent being to convey authenticity but a category mistake. The realised critic falls back on the word “I” rarely and selectively but when it is done it is done with a point. Thus: “I can only say that “All That Fall” in its localised richness has a humanity that leaves me more moved than by any other Beckett play.” To be moved: that is what it is for. Among the quotations Oscar is here. He speaks for a strand of today's theatre in “My play was a complete success. The audience was a failure.” As for the author himself the aesthetics of theatre are stripped down to 9 words that end the essay which opens with Mike Pearson. “Drama is, first and foremost, the art of contradiction.” critical comment ISBN: Faber & Faberpublished:

|

Looking for theatre books? Try the Internet Theatre Bookshop first                                  |

Who Keeps the Score on the London Stages?- Kalina Stefanova |

Critiquing the Critics

Critiquing the Critics This is a book that is different. It was published in the year 2000. The National Library does not hold a copy. The largest bookseller site has a few copies on offer, its price averaging £100. It was probably read in small quantities at the time; its appearance here is only because it turned up nine years ago on the shelves of the Oxfam bookshop in Aberystwyth's Great Darkgate Street. I read it in 2009 and, in this time for retrospection, again in 2018. Much of the content is anecdotal and forgettable. Nonetheless, even if its readership is likely to be narrow, its 210 pages hold much of interest. Kalina Stefanova won a Fulbright Visiting Scholarship to the Department of Performing Arts at New York State University. The year was 1990 and she was from Bulgaria. She followed the period in the USA with a British Council Scholarship to City University. From the USA time she published “Who Calls the Shots on the New York Stages?” This book is the British counterpart. Formally, it is made of 19 authorial questions to a range of theatre professionals. The answers, printed verbatim, are of varying length from a paragraph to a page. The range of interviewees is formidable, comprising 28 critics, 15 dramatists and directors, 5 producers and 6 publicists. Nick Hern, the sole publisher, also contributes. For an academic imprint Stefanova's approach puts empiricism before theoretical considerations. Her own direct writing is contained within an 8-page conclusion. Her judgement on the critical scene of her survey is “a very worthy and admirable model of theatre criticism- an exemplar of the golden middle way.” This middle way is one that distinguishes London from both USA and Europe. “Not a star who calls the shots, as is the case in New York. Neither a lofty scholar nor a biased insider, as is mostly the case in Eastern Europe.” The effect of formative years in pre-1989 Bulgaria is evident. The making of the book took place in another century. The Web had been in existence for eight years but was the domain of a small minority. James Christopher remembers the time before. At Edinburgh in 1986 the newspaper for which he was writing folded. He had the use of a photocopier and printed his own. In A3 format with a run of 1,000 the information had a value, priced at £0.20 a piece. These were different days. A minority of the interviewees hold teaching jobs in universities but most have a background in plain journalism. Jeremy Kingston at Punch was a restaurant critic for 6 years. Alastair Macaulay at the Financial Times did dance, then music before theatre. Jack Tinker was an exception. “When I was about 12, I decided I wanted to be a critic.” That journalism paid and the critics write about occasional flights to Moscow or Beijing. The rooting in journalism means that the prose has to readable. The fight for space and greater word-count is a consistent topic. Lyn Gardner: “good theatre criticism requires space but newspaper editors don't want to give it.” John Gross writes of the stylistic tradition: “English [sic] journalism is more casual than American journalism in general. English writing tends to be more personal, ironical and nuanced.” Matt Wolf, an American in London, points to the advantage here: “British critics have just seen more.” John Elsom provides a comment that does sound British. “The death of the critic is when they become slick, when they use the same adjectives or phrases, like the same things and lose any connection between the theatre and life. This could lead to a self-obsessed and rather masturbatory activity. Critics can easily become narcissistic.” The book does not take the lid of the theatre of Britain as a whole. It is London and Stratford. One of the interviewees comments on the resilience and vitality of regional theatre. It is theatre that is made from plays and dramatists. The Fringe gets small mention so it is a view from the centre. But then the centre is an impressive one. Relations between makers and commentators are mainly cordial. Michael Billington recalls the cuffing he received from David Storey, an incident that was amplified in the retelling. But more common is “there are at least half a dozen critics whose responses are intelligent and whose work I listen to.” Arnold Wesker says of the ones whom he rates highest: “you get a sense that they care about the theatre. If something excites them, it's a discovery.” Alan Ayckbourn: “the best criticism is written by those with a genuine love for the theatre who want to convey their enthusiasm to their readers.” Sir Alan has it. critical comment ISBN: Harwoodpublished:

|

Looking for theatre books? Try the Internet Theatre Bookshop first                                  |

Peggy to Her Playwrights- Edited by Colin Chambers |

The role that Peggy Ramsay (1908-1991) played in the theatre of Britain was both colossal and central. She also played a part in the history of theatre of Wales. At the time when Dic Edwards was the most performed dramatist on stages beyond Wales Ramsay was his agent. If Dic Edwards does not appear in this selection of letters it is because the wealth of playwrights that her agency represented astounds.

The role that Peggy Ramsay (1908-1991) played in the theatre of Britain was both colossal and central. She also played a part in the history of theatre of Wales. At the time when Dic Edwards was the most performed dramatist on stages beyond Wales Ramsay was his agent. If Dic Edwards does not appear in this selection of letters it is because the wealth of playwrights that her agency represented astounds.The starting list of 40 starts with Rhys Adrian and ends with Charles Wood. It proceeds through almost every dramatist who impacted the theatre of the era. The dramatists in translation are of the stature of Arrabal, Ionescu, Pinget, Vian. Adapters and translators are of the like of John Barton. Names of note not in this selection are Frayn and Osborne, Pinter and Stoppard but these few omissions are swamped by the legion whom she represented. Her prominence as an agent was unique to the extent that her presence jumped well beyond the small office in Godwin's Court. These revealing letters should be read in conjunction with Simon Callow's memoir of 1999. She can be traced as an inspiration in fiction in Ayckbourn's “Absurd Person Singular”, Peter Nichols' “A Piece of My Mind” and David Hare's “the Bay at Nice.” Vanessa Redgrave played her in the film of “Prick Up Your Ears.” Editor-selector Colin Chambers includes a letter of 8th May 1987 in which she asks John Lahr that she be removed as a character from his “Diary of a Somebody”. The correspondence reveals the sheer pace of a life at the centre of theatre's business. The schedule recorded for 2nd October 1968 covers a dress rehearsal of a client's play, a five minute gap for a 10:30 showing of another author's play. “Television was Work”, Simon Callow wrote in “Love Is Where It Falls”. The day includes a Gandhi prayer meeting and another TV play. The next is scheduled for lawyers, yet more TV drama before a weekend in Brighton loaded with scripts to be read. The leading quality that pulses through the letters is enthusiasm. 5th May 1967 she sees “Dingo” in Bristol and writes: “I was tremendously moved by it.” To the Head of Plays at the BBC 25th August 1969: “I know that Arden has the finest writing talent in England [sic] today and possibly in the English speaking world.” Her stance towards her clients, 22nd September 1969, is generosity. The agent's due to the playwright is simple- “to foster talent.” The letters touch on the solicitous. On July 1st 1970 she writes to the Ardens who had been briefly detained by police in Assam: “do be careful about going through your money too lavishly. I'm a bit worried that you'll be without sufficient means when you return.” To Robert Bolt, 18th July 1978, about a fellow writer: “Peter Nichols has just written a 6-part TV on his career which is full of hate and malice, and I've tried to tell him that without love and compassion an author is nothing.” Then as now distractions to writing are many. 3rd November 1981 she commends Howard Brenton for turning down an event at a US university: “Two of our authors, to say the least, are absolutely behind because they can't resist a free jaunt.” Simon Callow reveals the music she listened to at home. Zemlinsky and Schoeneberg were indicators of a deep cultural knowledge. In a letter, 24th October 1957, to Frith Banbury she vaults across de Maupassant, Quiller-Couch, Tennessee Williams, Marlowe, Baudelaire, Havelock Ellis, Ovid, Gide, D H Lawrence, Villon. Unsurprisingly, the book reveals dramaturgical depth. 19th January 1983 to Max Stafford-Clark: “Before I was an Agent I ran a theatre. A mistake over the choice of director, designer, play, actors and lighting was crucial.” In a studied letter, 14th March 1962, she advises Alan Ayckbourn: “you need a long sustaining scene to act as contrast between Act 1 and III.” She writes to Terry Hands, 3rd May 1974, about the challenge of staging “the Bewitched”. Peter Barnes is pitched between the Jacobeans and Laurel and Hardy. The result is “sheer naughtiness entirely lacking in sexuality or eroticism.” Writing for live acting is its own art. To Edward Bond, 14th August 1969: “Anyone who thinks that writing for the stage is in any way similar to TV, or that writing for TV has anything to do with films, is mad and incapable of judgement.” Even back in the last century she was noticing the decrease in the proportion of money flowing through to activity on a stage. “But no theatre will ever be entirely satisfactory until the money is put onto the stage, which is the reason for the theatre being there in the first place.” She advises against over-intellectualism: “there should remain something of the child to communicate with a mixed body such as one finds in an average audience.” Playwriting is no different from accomplishment in any field of endeavour: “talent isn't enough; work and self-criticism is essential.” “Peggy to Her Playwrights” is also a report from history. On 5th February 1964, in an uncharacteristic tone, she meets a director of the moment: “I lunched with Hall. It's terrifying to watch the effect of his maniacal will to power, which is almost destroying him. My God, why doesn't he read Schopenhauer and see the danger he is in.” In an unimaginably different climate the Ardens go on strike because they do not like what the RSC is doing with their play “the Island of the Mighty.” The loyal agent has private reservations but helps with legal advice and takes hot soup to the picket line. An agency is a business. Simon Callow was her executor and reveals the size of her estate in his book. It was considerable but her approach to money is consistent. On the one hand she mentions, 23rd February 1957, that after two years representing Robert Bolt: “so far I haven't earned one single penny.” But there are other times as on 28th February 1967: “On Friday evening I sold LOOT film rights for “£100,000!!!” But she observes the lures of success in the theatre. On 22nd January 1970 she writes of N C Hunter: “All his plays ran for years at the Haymarket, and the poor bugger is now stranded on the island of his past success, utterly forgotten, and a sad and embittered man. I met this ghost at a party a few years ago...he hadn't learnt a thing from all his success.” The theme is constant. To Bolt 4th December 1963: “once an author has become successful and famous, it becomes more difficult to speak the truth, and this is why people like Rattigan become bloodless, because, in time, people fear to give them anything but lip service for self-preservation's sake.” To Michael Elliott 23rd March 1962: “[John] Mortimer's big weakness is a passion for success, and the trappings of success.” She sees talent being drained: “the people who love successful people exploit them, take them up, throw them away, and sometimes only a shell is left.” She earned millions and the life was lived with hedonism but not ostentation. She wrote 11th August 1964 on earning enough to live satisfactorily: “we can all live more simply, and give ourselves time to think and feel and see. We don't need better cars, more clothes, bric-a-brac or luxuries. All these town houses, mammoth offices, fleets of secretaries, business lunches- ludicrous”. The film industry presents a particular temptation. To the enormously successful Bolt 5th October 1964: “you must live exactly as your audience lives, with all the concerns which we have all the time.” She makes the comparison with herself. “I often think the only reason I am doing well (financially) as an agent, is because I live the same way as the very ordinary man in the street.” Theatre is ever a cause for simultaneous elation and despair. The roll of dramatic talent that unfurls across the pages is awesome. But nonetheless in August 1971: “the West End is crammed with deplorable plays, led by so-called stars...and that goes for the Royal Court too who are the worst of the lot”. “No Sex Please We're British” is banking £7000 a week.” As for the critics a letter to Michael Billington, 16th July 1979, in defence of Wallace Shawn critiques his narrowness of criteria. A letter to Irving Wardle is a stinger of rebuke although signed off “affectionate greetings.” As for the press as a whole she reassures David Hare at the bad time of “Knuckle”: “F*** the critics”- all in capital letters- “They've all compromised or sold out...They are hired helps of perhaps the most disgusting press we have ever had.” historical surveys ISBN:978178684295 Oberon Bookspublished:

|

Looking for theatre books? Try the Internet Theatre Bookshop first                                  |

How Plays Work- David Edgar |

Description is often a better educator than prescription. There is not a charity shop that does not offer a stack of “how-to” books on painting and illustration. As primers they all have something of interest to say. But the jump is still huge when it comes to picking up charcoal or pastel to make form or meaning. Description needs to be what Ryle and Geertz called thick and its source needs to be that of a master. David Edgar has been in theatre, as practitioner and commentator, for 48 years and is such a master. “How Plays Work”, nine years old and frequently reprinted, is not just a primer but a refreshing and stimulating read in in its own right.

Description is often a better educator than prescription. There is not a charity shop that does not offer a stack of “how-to” books on painting and illustration. As primers they all have something of interest to say. But the jump is still huge when it comes to picking up charcoal or pastel to make form or meaning. Description needs to be what Ryle and Geertz called thick and its source needs to be that of a master. David Edgar has been in theatre, as practitioner and commentator, for 48 years and is such a master. “How Plays Work”, nine years old and frequently reprinted, is not just a primer but a refreshing and stimulating read in in its own right.The pleasure is in the punch of style, the breadth of reference and the company of the author. If he is austere even slightly alarming in person, in print he is generous and far-seeing. John Godber even receives a commendation for his mastery of a particular strand of play. Edgar's approach is low on theory and high on example. His concern is theatre that has fused with audiences. He cites a philosopher, Mary Midgley, but only as a comment on the nature of evil. He brings in the makers of rules from Aristotle and Vauquelin to Syd Field. Anthony Minghella took pride in “The English Patient” being used as an example of how not to write a script. The Robert McKee prescriptive formula, says Edgar, damaged BBC drama. McKee, he says, now accepts open and closed endings, multiple protagonists, non-linear time The eight brisk chapters are thematic: audiences, actions, characters, genre, structure, scenes, devices, endings. The theatre he draws on for illustration vaults the centuries. How Etherege, Goldsmith and Sheridan did what they did is still valid for today. But classics are outnumbered by dramatists of now: Crimp, Eldridge, Griffiths, Keatley, Lavery, Nichols, Penhall, Ravenhill, Shaffer, Shinn, Roy Williams are just a sample. Edgar writes a lot of theatre but manifestly sees a lot too. Critics' voices are used sparingly in “How Plays Work.” But he cites David Lodge, Michelene Wandor, Jonathan Culler where they are needed. Eric Bentley says all that need be said on the making of dialogue. Properly made dialogue serves four purposes simultaneously. Edgar, like Bentley, is a writer of tautness, his longest chapter being “Devices.” In his terminology “devices are mechanisms for conveying dramatic meaning within scenes...the device goes to the very heart of what theatre is.” The examples of practice that follow take in Rattigan, Shakespeare, Churchill, Pinter, Friel. As for structure it is simply a grid of time and space, within which the dramatist reveals connections. On the topic of the internal architecture of connection he finds a source who declares that scenes “must be knotted together in such a way that the knots are easily noticed.” The prescriber is one B. Brecht. If theatre is liable to be tussled over that is sign of a lively culture. But it is not a lecture podium- it shows but does not teach. If it has a purpose it is to reveal the distemper of the times not to prescribe simple-hearted remedies for amelioration. Edgar's references roam over genre. John Grisham's sixth rule is “Give the protagonist a short time limit. Then shorten it.” “The Magic Mountain” is a novel of greatness. Jay Parini once asked Gore Vidal “do you think I can have characters talking for fourteen or fifteen pages about history and aesthetics and that sort of thing?” Vidal: “only if they are sitting in a railway carriage and there is a bomb under the seat.” Edgar calls it the ticking clock. He shows its application in “Romeo and Juliet”, “Skylight”, “Poor Bitos”, “Plenty”, even Coward and “Still Life.” The reading of “How Plays Work” is a return visit, prompted by 2018's recent seeing of plays of contrasting success. It lives up to its title in full. critical comment ISBN: Nick Hern Bookspublished:

|

Looking for theatre books? Try the Internet Theatre Bookshop first                                  |

The Theatre and Films of Jez Butterworth- David Ian Rabey |

Rhug, in the upper valley of the Dee, has a well-known landmark, Wales' only public sculpture of a bison. On a blank-coloured Sunday in January I found myself in the car park, near the bison, in impromptu discussion with the owner of a neighbouring car. If the subject was writer Jez Butterworth it was not so surprising. Wales is small and companionate. The main routes in the north are few and five A-roads meet at Rhug. The conversation had a prompt, the other traveller being author of the only book-length study of Jez Butterworth. The book was published a couple of years ago and noted at the time as one to read. The accidental encounter was prompt to do just so.

Rhug, in the upper valley of the Dee, has a well-known landmark, Wales' only public sculpture of a bison. On a blank-coloured Sunday in January I found myself in the car park, near the bison, in impromptu discussion with the owner of a neighbouring car. If the subject was writer Jez Butterworth it was not so surprising. Wales is small and companionate. The main routes in the north are few and five A-roads meet at Rhug. The conversation had a prompt, the other traveller being author of the only book-length study of Jez Butterworth. The book was published a couple of years ago and noted at the time as one to read. The accidental encounter was prompt to do just so.Jez Butterworth and Martin McDonagh are both writers at the top of the tree and share things in common. Born a year apart, March 1969 and March 1970, they were successful at a young age. Butterworth's “Mojo” (1995) was the first debut play in a generation to be performed on the main stage of the Royal Court. McDonagh was at the National Theatre by the age of 27. Both have moved to span successfully theatre and film. Both have been the subject of a particular criticism. The 1990's McDonagh trilogy was critiqued for an inauthenticity in its rendering of Ireland. An Irishman from Elephant and Castle was felt not to be the real thing. A similar criticism is fired, a generation on, at “the Ferryman.” The critics adore it, the online world less so. Voices of Ireland condemn it as inauthentic. At the extreme its audiences are damned as complacent know-nothings, Brits who would return its border setting to the status of bandit country it held for so long. The critiques are probably true but they point to a paradox. “The Ferryman” is a theatre work of magnificence. Its formal qualities awe, its climax devastates. At the same time magnificence need not necessarily embrace authenticity. Returning to McDonagh, his Ebbing, Missouri is not a study in documentary accuracy. David Rabey addresses this aesthetic ambivalence early on in his crisp, lucidly written study. Just as the map is not the territory, the world on stage is not the world outside. Rabey locates the right critical voice, one which is particularly appropriate for Butterworth. In “Shakespeare's Festive Tragedy” (1995) Naomi Conn Liebler writes: “What is represented is not a “real” community, any more than the characters are“real” people. They are representational models designed to express the complex relations of an exemplary society whose story is frozen for examination purposes at a particular moment in its fictionalised history.” In extrapolation this means that a critical approach to “Jerusalem”, says Rabey, is different from an approach to Edward Bond. The book uses the phrase “political formalism” for Bond. Rabey is a university authority on theatre who is interested in theatre as drama, art even. He does not approach theatre as a vehicle to exemplify theories from Walter Benjamin or Guy Debord. He cites the good writing voices who were there in an auditorium to see plays performed by actors. He quotes from Aleks Sierz, Nicholas de Jongh, John Nathan, John Peter. Susanna Clapp has interesting things to say on director Ian Rickson. Charles Spencer is there for three hours of Johnny Byron in “Jerusalem” and simply sees “one of the greatest performances I have ever witnessed.” These critical voices add flavour and richness to the book. The critic is a first draughtsman of history's judgement. The university voice, a good one at least, takes judgement to a next plane. “The Theatre and Films of Jez Butterworth” was written before “the Ferryman”. One of its fascinations is how its assessment of the continuity in the Butterworth oeuvre prefigures the epic of 2017. Good writers also give insight in providing context and making connections. Rabey cites another strong academic voice who does drama. Michael Mangan recalls the vestigial pagan figures who overhang the work. No other dramatist is haunted in the same way by the Green Man or the Summer King, the Trickster or the fool-king. The book reveals a key influence on “Mojo” to be a Karel Reisz film, “We are the Lambeth Boys”. A critical contrast is made with David Hare's “Teeth 'n' Smiles”. The shadow of Beckett is everywhere in theatre. Rabey points to a difference; the shambling duo in “the Night Heron” discover decisiveness. The theme of sacrifice links Butterworth to David Rudkin's “Afore Night Come” and as far back as Sophocles. “Jerusalem” is revealed as gradual in its making. Discussions with Ian Rickson and Mark Rylance mattered. Butterworth went to Ted Hughes, the “tougher, fiercer poems”. The chapter “Fairy Tales of Hard Men” digs deepest as to why Butterworth commands the theatre of today. The work is about “frictions between members of a community who have conflicting senses of entitlement.” It is no surprise that the setting of County Armagh called. The Edgelands, to which Rabey refers, are locations that unsettle. The themes are “the rituals, transformations and sacrifices by which the male gender distinctively attempts to negotiate development and meaning.” The results are inevitable in plays that “examine the messages men hear about what is traditionally expected of them”. These edicts “prove fragile, restrictive, self-contradictory, self-defeating and self-destructive”. In the book's aim to unify the work thematically Rabey pinpoints “a consistent, but increasingly overt and central, purposeful mythic quality”. In his last action Quinn Carney, combining self-realisation and self-destruction, becomes suddenly and dramatically Hamlet . The title of the book is revealing. Its theme is the theatre, not the plays, of the author. A new opportunity for an audience to make its own judgement occurs this summer. “Jerusalem” receives its first revival at the Watermill. critical comment ISBN: Bloomsburypublished:

|

Looking for theatre books? Try the Internet Theatre Bookshop first                                  |

Other People’s Shoes. Thoughts on Acting- Harriet Walter |

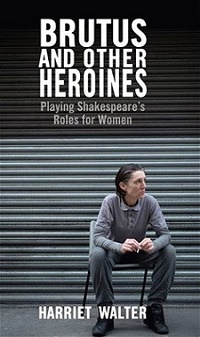

The reading of “Brutus and Other Heroines” in January was prompted by gender and representation dispute. It was also a reminder that Harriet Walter is author of a book on acting. “Other People’s Shoes. Thoughts on Acting” dates back to 1999 but has been reprinted several times. Like Simon Callow's “Being an Actor” Harriet Walter's book on acting holds up well.

The reading of “Brutus and Other Heroines” in January was prompted by gender and representation dispute. It was also a reminder that Harriet Walter is author of a book on acting. “Other People’s Shoes. Thoughts on Acting” dates back to 1999 but has been reprinted several times. Like Simon Callow's “Being an Actor” Harriet Walter's book on acting holds up well.Stage acting awes and the more it is viewed the more it awes. To read about it is like one of those fractals devised by Benoit Mandelbrot. To home in on a detail of the complex patterning does not make it simpler. It just yields a new complexity, albeit at a closer level. Which is not to mean that books by actors are not worth reading, because they are. The good ones have the effect of making the awesome more familiar, even if no less awesome. The clue is in the word itself. Acting is that- it is a sequence of acts over time and across space. Language is a different category, a symbol-rendering, encapsulating, abstracting process outside time and space. When writing turns to acting, it can only aspire to be a rough simulacrum. In this linguistic circling around the uncatchable Richard Eyre in interview with Judi Dench asked: “Is it difficult to talk about acting?” The actor's response: “I don't think we should talk about acting because there's nothing to talk about, really. It's as if we are blank canvases. It's the play and the author and the author's intention that energise the actor. It's only when you're telling the story that you're doing your job; after you've done that there's nothing really to talk about.” There is something to talk about. Harriet Walter writes of the art where the self yields up its fixedness of being itself. “Since I was very young”, she remembers, “I have been able to watch someone and imagine myself inside them, moving their limbs, striking their poses and by some strange mechanism, getting an inkling as to their feelings and thoughts.” But she runs up against the limits of description. “It's hard to explain how it's done because it is not a systematised process; it is just part of our equipment.” The genesis of every actor is its own. The book is not an autobiography but she is sharp on the differences and the commonalities in her parents. “What they also shared was a well-concealed but deep lack of self-confidence.” The adult child sees a common cause: “both had a dominant parent who had given them a sense of failure.” The effects of separation and private school in her own experience are dealt with economically. She writes of the elasticity of the teenage persona: “I started to capitalise on my versatility, being one thing to person, one thing to another.” Christopher Lee is revealed in a single line as an uncle. She adds an elliptical accompanying sentence. Lee's “own career, though relatively blessed, has never been anxiety-free”. She is modest on her own career. A turning-point is 7:84. She has an early job in Lancaster and 7:84 visits. John McGrath leaves her his telephone number and later, out of work, she calls. Of her experience with 7:84 she writes of the demands on the actor. “I had to coarsen up my act, broaden my humour, put over a rowdy song.” She joins Joint Stock and plays a male apprentice. “I had spent most of the evening under a table scraping out paint tins, and yet I remain prouder of “The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists” than of most other shows I have been involved with. The reason for this is simple. We had time. The show belonged to us all. Every experience in the last six months, whether ordeal or treat, had bound our imaginations together and this informed the quality of the work.” William Gaskill was the director for that production and she has particular observations on the director role. “The absence of a strong director breeds insecurity and fear”, she writes, “which in turn brings out the worst in people. If you cannot trust the Overseeing Eye, you compete for attention. Over-acting and upstaging...it is not a question of malice towards the other so much as a fear for oneself.” As for the role of leadership “there is an important distinction to be made between power and authority...power comes with the position, but authority has to be earned...we need the director's authority, but we can be messed up by their power.” The reports from the rehearsal room are illuminating. “I have taken part in useless time-wasting improvisations and I have witnessed near-miraculous ones.” “We worked on obsession and status, and these exercises went a long way towards unlocking the play.” Out on the street the actor observes other people. “Which part of their anatomy leads them? Their nose? Chest? Chin? Knees?” There are useful keys to unlocking another person. “Look for the fear” she advises, “fear is a great clue to psychological motive.” She observes the different media. The camera offers the solidity of recording performance. But theatre leads. “When we sit in the audience we don't just watch a fait accompli, we are part of the event. We remember the play as a personal memory. It is something that happened to us.” A permanency of discomfort is essential to maintaining artistry in acting. She observes actors who become habituated. “Clinging to your method can become a security blanket and actors are not supposed to be secure.” She describes the personality as “a ravelled muddle” but ends on a note of harmony. “I have been victim, neurotic and clown, and in playing out these extremes have settled on my true mien...belatedly become an adult who is relatively happy in her skin.” These “Thoughts on Acting” are illuminating and informative; they are also engagingly likeable. It is a book that has deserved to last. Acting ISBN: Penguinpublished:

|

Looking for theatre books? Try the Internet Theatre Bookshop first                                  |

Sweetly Sings Delaney- John Harding |

It is the way of the touring calendar that too many productions arrive over too short a time. In February, two productions were performed at different locations in the west on the same day. The advertising for one declared its foremost quality to be that it was “cinematic”. Since the arts of cinema and theatre have small overlap the advertising acted as anti-advertising and sent me to the other.

It is the way of the touring calendar that too many productions arrive over too short a time. In February, two productions were performed at different locations in the west on the same day. The advertising for one declared its foremost quality to be that it was “cinematic”. Since the arts of cinema and theatre have small overlap the advertising acted as anti-advertising and sent me to the other.As an episode it came to mind in the reading of John Harding's absorbing book. The film of “A Taste of Honey” is a regular on television. As a film it is lifted by Walter Lassally's superb photography and the Tushingham-Melvin acting partnership. But it is far different in flavour from the play that propelled the nineteen old Salford writer to fame. Among other things, “Sweetly Sings Delaney” reclaims the play for its place in theatre. Most first writing for theatre involves the playwright working their way through their admirations. With Shelagh Delaney it was the opposite. At the Opera House in Manchester she saw Terence Rattigan's “Variation on a Theme” and disliked it, thinking she could do better. The result, written in a matter of days, was sent to the Theatre Workshop in Stratford East. Gerry Raffles said of “A Taste of Honey”: “Quite apart from its meaty content, we believe we have found a real dramatist.” In the ever competitive atmosphere between the two innovating theatres the production programme took a swipe at the Royal Court. Their dramatist was the “the antithesis of London's angry young men. She knows what she is angry about.” Then as now, there was no shortage of aspiring writers for theatre. The Salford City Reporter of 9th May 1958 quoted a Mr G Raffles: “we have had 2500 plays sent to us in the last five years and this is only the fourth we have accepted. The love scenes are amazingly frank and a scene between the girl and a Negro boy is brilliantly written.” Behind the scenes, Joan Littlewood was frank on what she saw as the play's deficiencies. The dialogue sparkled but she considered many of the scenes undeveloped and the plot anecdotal. The solution in the production was to use direct audience address and to put a jazz group on stage. Johnny Wallbank's Apex Trio provided each character with a signature motif. The play vaulted to the West End in January 1959 and played for 368 performances. Broadway followed and John Osborne bought the film rights for a then weighty £20,000. Tony Richardson's film went on to win, among other awards, Best Actress and Actor awards at the 1962 Cannes Film Festival. Its status stands as the most performed play by a post-war British woman playwright. “Sweetly Sings Delaney” combines the virtues of slimness with fullness. Undogmatic and untheoretical, John Harding roams across an array of contemporary sources. He revisits the records of the Lord Chamberlain, the licensor of theatre in its days of censorship. The Lord Chamberlain's assistant, a Brigadier Norman Gwatkin reports: “I think it's revolting, quite apart from the homosexual bits. To me it has no saving grace whatsoever. If we pass muck like this, it does give our critics something to go on.” Its licence was granted with the word “castrated” taken out and a self-revelatory speech by the gay character Geof removed. Over at the Arts Council Drama Panel Harding finds an opinion that “it seems to have been dashed off in pencil in a school exercise book by a youngster who knows practically nothing about the theatre. Miss Delaney writes with the confidence of sheer ignorance.” The Daily Mail's critic took the same line, saying the play exuded “exercise books and marmalade” and that any “similarities to real drama are quite accidental.” The media was delighted to have a West End playwright of apparently genuine working-class background. The Daily Mail described Delaney as “wolfing down a meal of sausage, cabbage, beetroot and weak tea.” In a true indicator of another era the News Chronicle viewed her as “like a kennelmaid on her day off”. The Evening Standard reported her as having started smoking at age six. But in the nature of writers there was rather more ambivalence to her than these simplifying labels conveyed. Her work appeared to include being assistant to a photographer. In the letter she wrote to Joan Littlewood to accompany the script she said that two weeks previously she “didn’t know the theatre existed”. Journalists saw a cultural background in music hall and visits to the cinema three times a week. The truth was that she had worked as an usher and regularly went to plays with a friend, artist Harold Riley. He said he was “struck at the time by the extent of Delaney’s knowledge of the history of the theatre”. Joan Littlewood offered her young playwright guidance. “Read a good play,” she wrote “an Ibsen for example, then analyse it, note the construction. Playwriting is a craft, not just inspiration.” The next play “The Lion in Love” did not match the first and her writing life moved to short stories, radio and film scripts. Delaney is a crucial part of the story of Lindsay Anderson. In “Charlie Bubbles”, directed by and starring Albert Finney, an acclaimed writer makes a return to northern roots. Finney too came from Salford and Harding begins his book there. His Salford of the 1950s is a report from a world gone. Its lack of sunshine was due to sulphur dioxide concentrations that were twice those of neighbouring Manchester. The incidence of bronchitis was twice the national average. Over 1955-65 more houses were demolished per capita than in any other city. It was not just bad housing that went, but civic buildings with communal function, cinemas, churches, banks, department stores, pubs. Salford though had small affection for its writer. “A taste of cash for Shelagh but a kick in the pants for Salford” ran an early story for the Salford City Reporter. The film “the White Bus” was yet “another slur on Salford's good name”. Eras change; in 2014 Salford City Council organised the first Shelagh Delaney Day. critical comment ISBN: Greenwich Exchangepublished:

|

Looking for theatre books? Try the Internet Theatre Bookshop first                                  |

Brutus and Other Heroines- Harriet Walter |

Everything that is new is new in its own way. But nothing is ever entirely new. When Nietzsche wrote about eternal recurrence he was right, albeit not quite in the right way. Cultural life is normally quiet, as much in England as in Wales. In January there was a flare-up. It was unsatisfactory in that an issue was raised that was deep and felt. But it went without continuity and without continuity there can be no resolution. One national arts company participated in a manner that was eloquent and forthright. Another held its silence. Alfred Hirschmann wrote in 1970 on the choice between “Voice” versus “Exit.” The thing with silence is that it also speaks.

Everything that is new is new in its own way. But nothing is ever entirely new. When Nietzsche wrote about eternal recurrence he was right, albeit not quite in the right way. Cultural life is normally quiet, as much in England as in Wales. In January there was a flare-up. It was unsatisfactory in that an issue was raised that was deep and felt. But it went without continuity and without continuity there can be no resolution. One national arts company participated in a manner that was eloquent and forthright. Another held its silence. Alfred Hirschmann wrote in 1970 on the choice between “Voice” versus “Exit.” The thing with silence is that it also speaks.Surface symptoms mask deep issue. The issue of who gets to represent whom in performance is perennial. Its actualisation at any one time is a mix of expediency, convention and the decisions of those in power. In 2000 Hytner directed Gambon in a play by Nicholas Wright called “Cressida.” It was the subject of that play and the period of its setting was the year 1600. The latest chapter can be dated to 1992 and it involved two Richards. Richard Ingrams led the charge in fulminating against Richard Eyre. Clive Rowe could be a Damon Runyon chancer but Eyre's casting of him as Oscar Hammerstein's Mr Snow was an instance of a director going too far. It was a new chapter but not a new issue. In 1960 the New York Times inveighed against Sid Caesar's representation of East Asians. In 1936 Orson Welles' casting for Shakespeare earned it the sneer of the “Voodoo Macbeth”. Nothing is ever entirely new. Harriet Walter's latest book is thus timely. This season a group of women actors are at London's Bridge Theatre plotting a coup d'etat against power. Adjoa Andoh, omitted from the short press reviews of “Julius Caesar”, is mesmerising as Cascar. Michelle Fairley is a fine companion as Cassius. Yet the blogosphere is unhappy. “I'd assumed Fairley and Andoh were playing men, but this seems to suggest Cassius is female” says one “Sorry to niggle, but while I'm fine with actors playing across gender I'm not knowingly going to any more productions where the gender of the characters has been altered.” “I'm not at all fine with actors playing across gender- if the characters ARE men/women then they should be played by men/women.” In these commentators' eyes they see women before they see actors. Harriet Walter's subtitle is “Playing Shakespeare's Roles for Women”. Its ten chapters cover Ophelia, Lady Macbeth, Portia, Beatrice, Cleopatra. But the last 53 pages are devoted to the playing of men. Her Prospero which she performed in London and New York is not included but Brutus and Henry IV are. Phyllida Lloyd took her company into Holloway Prison. Harriet Walter discovers that the crimes are nearly all petty. “Nearly all women in jail are there” she writes “because of a man in their life: a pimp, a drug dealer, or a violent partner.” The workshops tell her one thing. “We did get confirmation that the play was the right one to do.” When it is over she concludes “I hoped we had done “Julius Caesar” justice, but I also felt we had left them with a sense of the talent we waste when we sideline swathes of society or lock them out of sight.” When it comes to Henry IV it is a big production. The cast of fourteen is “composed of women of all ages, sizes, colours and sexualities, some of African, some of Caribbean, Chinese or Indian descent, some Irish, some Scottish, one Spanish.” The production has a result for the actors in “that the women do not inhabit familiar categories.” Again the women of Holloway give insight. The prisoners see in Falstaff and the Prince the relationship of dealer to user. “Thanks to the prisoners” she acknowledges “we adopted this story as our input.” As for the transfer into maledom Harriet Walter is as good as any actor has been in print. “Playing men was not so much” she observes “about putting on deep voices or blokeish walks; it was more about stripping away feminine gestures. We found so many of our cultural habits...were about accommodating other people and making ourselves less threatening. We tried to get into a mindset of entitlement; entitlement to be seen and heard. To take up space and dominate a room.” “Brutus and Other Heroines” is not just about acting and gender. It is also about Shakespeare and it ends with a five page letter that starts “Dear Will.” “The women in your plays often have a moral clarity that comes from their very exclusion.” Among the characters and the actions she cites much of the verse and values highly the words of Brutus. “The abuse of greatness is, when it disjoins remorse from power.” Before it all begins she asks herself a question “could I risk a bit of bloody criticism from my male colleagues and male critics?” The answer here in print is “Of course I bloody could." Acting ISBN: Nick Hern Bookspublished:

|

Looking for theatre books? Try the Internet Theatre Bookshop first                                  |

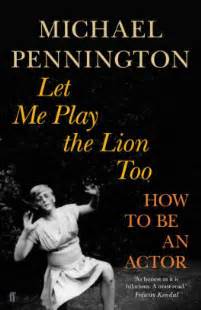

Let Me Play the Lion Too : How to Be an Actor- Michael Pennington |

When Radio 4's “Front Row” wished to pay tribute to Michael Bogdanov their first call went to Michael Pennington. It was Pennington who provided the most telling phrase for his collaborator-friend “an extraordinary mixture of scholarship and mischief.” The English Shakespeare Company, which they co-founded in 1986, features in the actor's 410-page book. It was a challenger to the RSC and National Theatre's in its ability to mount large-scale classical drama. Its funding, says Pennington, was “a happy conjunction of judgement, hunch and the right political moment”.